By Rem Jensen

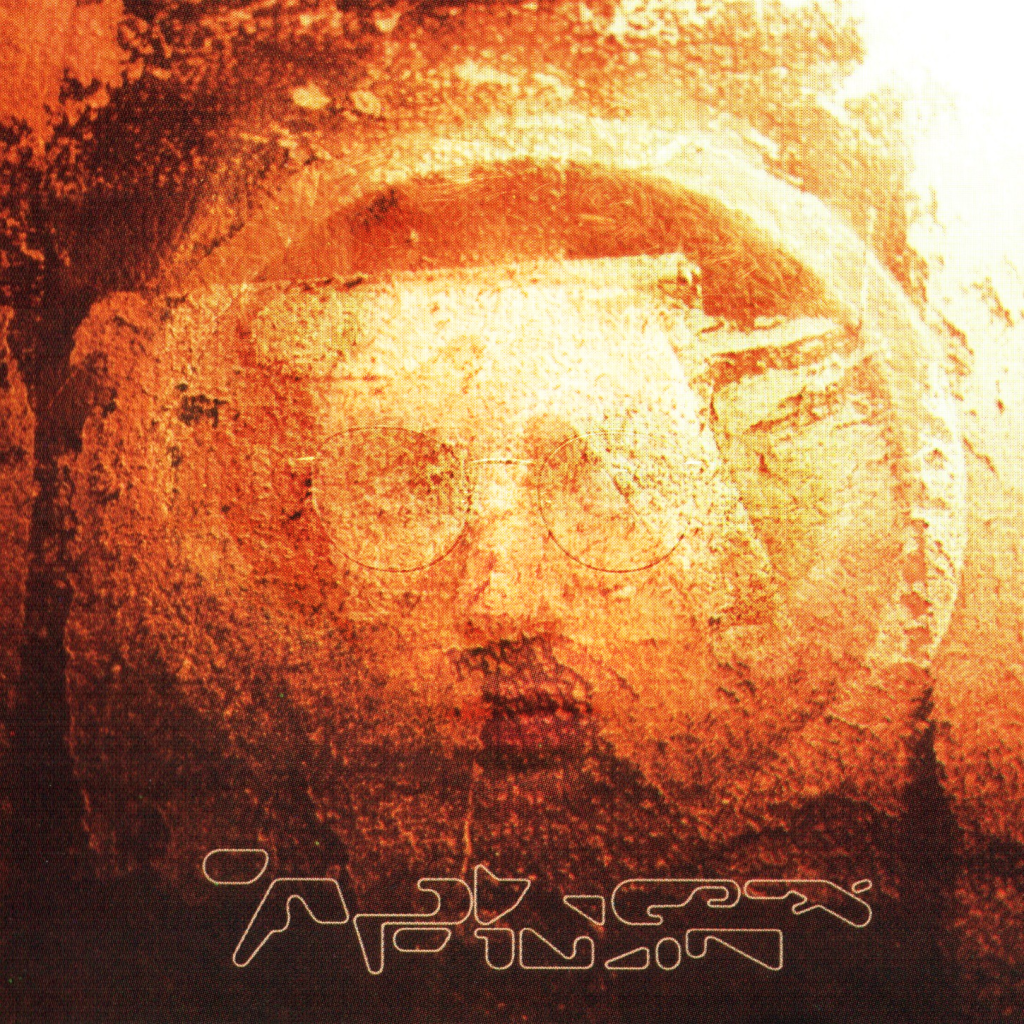

Over the course of a near 30-year tenure, the work of Phil Elverum has long stayed consistent in its themes of nature, emotion and vicariousness. Shadowed poetic phrases, fuzzy uncanny landscapes and questionable fidelity choices seeped from the delicate vocals, lo-fi guitars and bombastically mixed records put out via the Microphones project and the second phase of his work under the Mount Eerie name. Two records stand out among most listeners’ memory: the blown-out psychedelic folk masterpiece the Glow pt. 2 – released under the Microphones moniker in 2001 – and the emblazingly sorrowful lamentations and depressing grieving machinations of Mount Eerie’s A Crow Looked at Me from 2017.

Besides these two significant records, most others also stand out as important in the discography, such as the transformative 2003 record Mount Eerie by the Microphones, which cannot be understated in its formative impact as the momentum shift between the two projects, with long, expansive songs in many separate parts where the atmosphere is brooding, the narrative is gripping and the instrumentation even more palpably hypnotic. Another addition that’s worth mentioning is 2009’s Wind’s Poem, which the witch’s cauldron it was brewed from stewed a dizzyingly entertaining mix of post-rock, folk, ambient, nature sounds and even some flourishes of black metal thrown about. We would also be keen to mention The Microphones in 2020, the only other full-album return to the Microphones’ name, which acted as a reflective moment for Elverum, archiving in culminative prose the trajectory of his musical career and the changes in his life within and around the music. Which brings us to 2024 and his first record in four years, Night Palace.

After a handful of listens, it’s clear this is one of Phil’s strongest, most realized projects to date, with some different and capturing takes on old classic tropes found in the Anacortes artist’s audio arsenal. As a rite of passage of being an album in the Elverum discography, we have at least a nod or two toward previously established moments in his catalog: “The Gleam, Pt. 3” being a continuation of the Gleam series featured on 2000’s It Was Hot, We Stayed in the Water and on the previously mentioned the Glow pt. 2 and a small inclusion of the words “my roots were strong and deep” on the goliathian penultimate track on Night Palace, “Demolition,” referencing another track on the Glow pt. 2.

Not only are countless of these songwriting moments some of Phil’s most comprehensively structured and self-referential works to date, but Night Palace juggles adjacently familiar, yet eye-catching shifts in genres and sound compositions, an un-shy muscle undeniably flexed before by the K Records veteran.

At an 80-minute-long runtime, Night Palace keeps the listener glued to their speakers by way of Elverum’s chiaroscuro methods of compiling this 26-song adventure into a cohesive, effective and to this reviewer’s best definition, evocative exploration of the sonic expressions of life in the Pacific Northwest and introspective, content adulthood and the miasma of multitudes one harnesses at a developed, experienced age, with Phil nearing 46 – an age that he lyrically includes on the previously mentioned cut, “Demolition.”

An example of the breadth displayed on Night Palace are the multiple tracks that utilize the motorik beat, like on “Empty Paper Towel Roll,” where Phil illustrates viewing the sky through a narrow circular field, eliciting the feeling of a tangible slice of the universe, much more digestible and disassociable than the vehement world that bears down on all who live inside it, by way of the foresty approximation of its Yo La Tengo-like sugary noise-pop remnants. Another krautish track, “Non-Metaphorical Decolonization,” the final single for the record itself, immediately engages the listener with its robotically precise rhythms and droning shoegazey tone that call to mind some work by Radiohead or My Bloody Valentine, of which it lays somewhere in the middle of the former’s driving drum patterns and the latter’s wall-of-sound washed, crunchy chords, not before culminating into a true Elverum solo acoustic fresh breath in, before exasperatedly breathing out into a large yet intimate full-band ending.

Some little quirks within the confines of this double LP that I feel worth noting are as follows: the short stint of free-improvisational blastbeats and screams à la Naked City on “Swallowed Alive;” the obliquely introduced trap triplet drum machine hi-hats on “I Spoke with A Fish” that emerge only for five bars; the massive, cacophonous drone walls appearing on the back half on “Co-Owner of Trees” that sound more Sunn O))) than the Stereolab adjacent kosmische jams that appear on the first half of the track; the watery walls of white noise on “I Heard Whales (I Think)” that harken back to the transitional moments between tracks on the aforementioned Mount Eerie record from ’03; the thudding production of the drums and the discordant harmonies on “Breaths” that remind me of the resonant reverberations shown on records produced by The Body or This Heat.

In typical Phil fashion, however, the majority of Night Palace washes with his predictable – yet not overindulged – combinations of guitar distortion, cozy vocal swells, dry acoustic drum kits and delicate, shrugging, introspective writings that would not be out of place in a skunk-swallowed, sweat-dripping dark cabaret. These tracks are cumulative of that ’90s indie sleaze sound of Dinosaur Jr., Pavement, Elliott Smith and other groups of which Phil has shown some outward appreciation; “I Saw Another Bird” spurs the thought of the Smog song “Cold-Blooded Old Times,” and “Broom of Wind” itself conjures the Silver Jews track “People.” Even more so, both external group frontmen Bill Callahan and David Berman have been seen at one point in time in the same room with Phil, as if their similarly fleeting tunes and mutually mundane invitations felt the gravity of one another and pulled each other into an amber-lit, quartz-surrounded box, and prospered a discussion I imagine involved innocuous discussions about pollution, milk substitutes, guitar tunings and dialogues that stitched together Hemingway, highway patterns and Hellmann’s mayonnaise.

Returning thrice to the track “Demolition,” the sprawling 12-minute song has its sails gusted by continuously whirring wind sounds, as Phil wanders about like a held-hand child showing the adults the world it lives in; with the tasteful verbiage of McCarthy, the introspection of Camus and the tempo of Plath, it’s a track where the length allows the listener to step into a murky, Twin Peaksean dreamscape, beckoned by the narrator’s orations of cabin life tucked away in copses within copses, nihilistic ruminations on the nosediving state of the world’s climate, optimistic outlooks of a far-away future that’s healed from the self-inflicted scars of human wreckage and the power of a islandic meditation retreat that left him a shell of a skeptic. The insularly alienating multi-tracked vocals speak as a hipster worm burrowed in your brain, the instruments sparse as wind chimes swung by sea breeze and the effervescently airy drones and minimal ritualistic percussion that bookend this song, all add up to an effort that deservingly envelops much of the D side of Night Palace.

As the 21st studio effort in Elverum’s catalog, it’s indicative of the prowess of the Washington native, and how able he is to tap into repetitiously routinized, well-established and fundamentally simple writing predilections and expectations, yet still with the ability to say something new, write something new or even conjure new images of still-life paintings that have been gathering dust somewhere in the labyrinthian confines of a House of Leaves-esque overgrown mansion, breathing with life forces inherited from eons’ worth of civilization, evolution, growth, destruction, rehabilitation, resplendent forests, weathered hearts, slimy inlet stones and the pulsating creaks of wood that outlive many of our own lives, ever alive and animated by the souls that have been birthed and swallowed by the bear hugs of time.

Night Palace serves as a beautiful, competent confluence of little sprinkles of artistic variability, sandwiched between the conventional Elverum writings that again feel like continuations of his well-established singer-songwriter sound, but achieved through a much more mature, intentional and calculated approach to a style that at its core in both initial writings and final products are commonly nothing more than a man with six strings and a hollow body, crooning away soft écritures of lovers, expeditions, analogies and a continual underlying connection with thee Mother Earth.

I hope you’ll be as excited as I was to learn of a Mount Eerie performance coming to town in February of 2025, one of which I’ll be at the front row of, with eyes as wet as a Sauna, pupils as large as the Moon and neurons that fire at near the temperature of the Sun.